- Parkorama

- Life and Story

- The constructed truth of the story

- Borderland

- Body Therapy - an introduction to Johnsen and Nielsen

- Monkey wrenches, balloon animals and other ambiguous elements

- Construction in space

- Risking reality

- Excerpts from "Manual til samtidskunst"

- Blind Walk

- View-feminist strategies

- At the Fence

Risking reality

The videos of Birgit Johnsen and Hanne Nielsen

Art historian, Art Critic, Gitte Ørskou Madsen

Translation Astrid Aagaard

There is something spectacular and at the same time redeeming about the videos of Birgit Johnsen and Hanne Nielsen. Spectacular because at times their humour is so black, that it is on the verge of being provocative, and because the narrative suspense used by some of the videos has traces of the compelling fiction of feature films. And then at the same time redeeming, because there works stem from an already familiar reality, which we know so very well from our own everyday life, and which Johnsen and Nielsen use as their artistic material without lapsing into technical seduction. Often the camera is still, silently registrating, without interpreting the strange events, which unfold in front of it. It may be an almost banal reality captured on the screen, but at the same time it is remodeled, placed in a new system, which make us stop in wonder, trying to understand the logic in the actions. As in the video Afrivning af løg (Grinding onions) from 1995, where already the title, although with a twist, hints at the pleasant familiarity of a housewife action, which during the video is transformed into something painful, bordering on the psychotic with its compulsory rhythmic. At the beginning of the video, the two artists are sitting next to each other with an apathetic gaze, staring into the camera, both with a grater in the lap and a pile of peeled onions lying in front of them. The action of the video starts when the two women seize the onions, and grate them one by one. The onions are transformed into a squashy substance in the laps of the women while their faces are slowly dissolved by tears and snot, yet without them ever turning their stare away from the camera. The video stops when all the onions are grated, and the rhythmic scratching from the grater is replaced by silence.

It is a grotesque example of a housewife's daily pursuits we are witnessing here, maybe urged on by woman’s cursed conscientiousness - she is not satisfied until all the onions are grated, despite the visible physical discomfort. The gender of the artists is not entirely unimportant in this connection, because it is a typical female occupation from the close environment of daily life, which forms the drive of the action, removed from an all too well-known everyday setting and inserted as a piece of artistic material. But at the same time the action contains a well of symbolic interpretation-possibilities, juxtaposing the video with the traditional allegorical work of art, known from the history of art as a figurative representation of an abstract concept. Perhaps we are presented with an image of human decomposition, caused by the monotony of life, and made literal by the grating of the onions. The French thinker Roland Barthes thought the onion an obvious metaphor of his view on the semantics of a piece, because according to him the meaning of a work is not always revealed in the depth, but is often found in the actual structure of the surface. If we peal the onion it appears that that which is hiding under the surface does not bring about new perceptions, but is only a repetition of what we already pealed off.

The same strategy seems to be lying behind the works of Johnsen and Nielsen. They display a seeminglyrecognizable and banal reality, which is suddenly changed to a both funny and grotesque scenario through very simple moves. This allows us to base our interpretations in as well our own everyday experiences as the symbolic and theoretical discourses, which at the same time cross swords in the works. Still there is no faded symbolism hiding behind the different layers of meaning in their works, because as in Afrivning af løg the meaning is lying right in front of us, in the almost touching banality of the action and the insistent realism of the scenario. The consciousness that the onion actually does start off the lachrymal canals does really not require any other insight than what you get through everyday life, and which is simply taken for granted by Johnsen and Nielsen. Where art has often tried to remove itself as far from reality as possible in order to approach the spirituality and the sublime experience, Johnsen and Nielsen insist on the naked and undramatic reality of everyday life as their material, which in their works are staged in new, surprising constellations. "Trivial", you could call it, without falling into a simplepopularism. Because through letting us believe, that we know what we see, Johnsen and Nielsen are drawing away the carpet under us at the exact point where things turn out to be something completely different.

Take for instance the white rabbit. It appears several times in the works of Johnsen and Nielsen, both as the main character Miss Long-Ear in the grotesque tale Rabbitsuit and as the innocent victim in the strange Attributes. Initially we recognize the white rabbit as a sign from the already existing reality, where its magical aura comes from its role as the item being drawn out of the magician's hat, while it for many little girls is a living variety of the cuddly bear. But in Attributes from 1997 it has been hung, ready to be flayed and cut up. A pair of male hands slowly skins the fur off with a knife, while his voice gives an instructive and technical explanation of the skinning. Behind the fur the meat is appearing, and for a short moment we shiver at the sight of this piece of nature, with roots in that everyday work of the hunter which basically constitutes the action. The white rabbit is literally being ripped off its cultural clothing as cuddly toy and is driven back to its natural element. Having accepted this metamorphosis, the point of the video seems reliable, perhaps even morally correct.

And then the same male hands place the skinned rabbit on a table, where its fragile body is dressed up completely in doll clothes. Suddenly its limp, meaty body looks like that of a baby, and the hunter's previous rather tough and unsentimental skinning is changed into a nursing situation, usually connected with caretaking. The morbid overtones of the situation do not deny themselves.

The rabbit is transformed into a baby, the logical to the grotesque, and we are thrown back into a comprehensional void, which we are otherwise kept out of through our cultural education. It is all about nature and culture - a round trip so to speak - because the cultural significance contained in the white rabbit is torn away through the skinning, only to be forcedonto the dead body through the painstaking dressing up in pretty dolls clothes.

Again we are dealing with an image, which is both spectacular and redeeming at the same time, even in its most grotesque form. We are met by a piece of reality and in this lie both the spectacular and the redeeming. Immediately a white rabbit is present in a very touching way, while skinned and dressed up in doll clothes it is changed into something completely repulsive. The wellknown is transformed into something unknown - or, as stated by Sigmund Freud, das Heimliche is transformed into das Unheimliche. The paradox is, that what in reality is real, and which Johnsen and Nielsen show us without any nonsense, can not be consumated as real, because we have never seen it before. The real is, however backwards it may sound, apparently always a construction and fiction. While for instance the abstract painting, in seeking to withdraw from reality, postulates to contain a spirituality, which is not meant for reality, reality must be content with being categorized as second rate, inert and material and without transcendence.

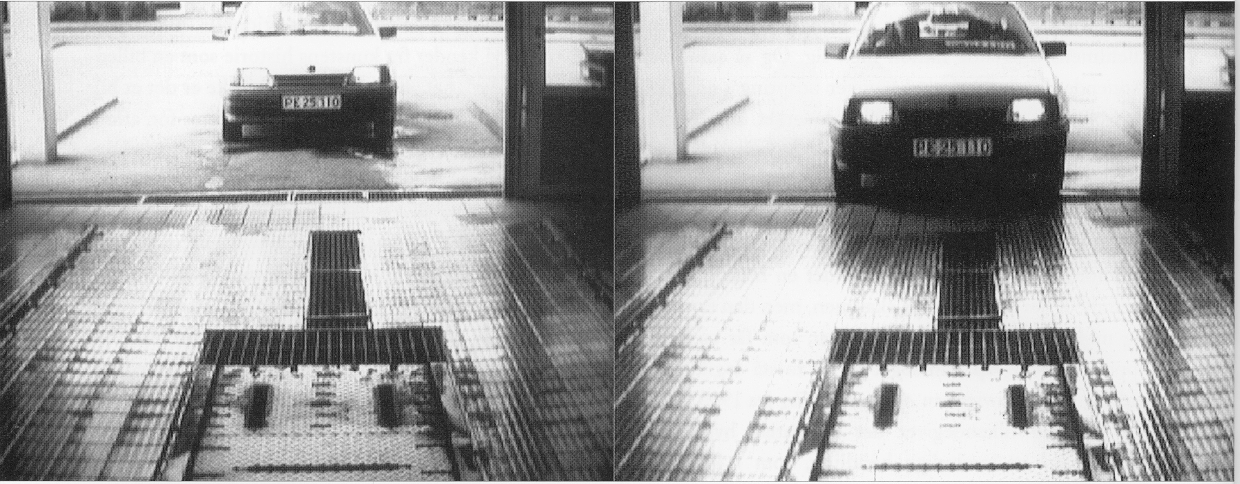

It is this classification which Johnsen and Nielsen, according to me, are trying to make up with. They display the most banal, gives it a grotesque twist and insist that we can find greatness in the small, the spiritual in the material. In the installation Car Wash from 1999, where a number of smaller and completely un-cool cars constitutes the main motive, we are taken into the car wash through the video, while a well of photos and slides, some even computer manipulated, present the nine cars as heroic images of a status and a potency which they basically do not posses. During the actual car wash we are taken to the drivers seat, from where we watch the big orange brushes, which, as they slash against the windscreen, remind us more of a painting by the American artist Mark Rothko, who claimed that he could visualize the sublime, than the languid daily action which the car wash is also. However, the setting allows us to read allegorical elements into the video, which at once becomes an image of the artistic process, where a cleansing of the idioms carries it forward towards the sublime. In this way we have got the opportunity of both recognizing the car wash at the service station and at the same time read an interpretation into it which derives from our cultural education.

The co-existence of the banal and the sublime in one and same motive has become the artistic feature of Johnsen and Nielsen. They dare to acknowledge that they are deeply rooted in a material and at times trivial reality. Rather than trying to escape it, they use it abundantly in their works, which bring out both smile and horror through their insistence that the spectacular and the redeeming, the fictive and the real, are two sides of the same matter. Their work is both sympathetic and shocking, and because they insist that reality is their material, their work is a valid bid on a modern artistic position, where the transformation of the artistic material is not meant to liberate itself from the reality of the spectator, but on the contrary lures the spectator towards itself under the cover of being presented as something familiar.